When it comes to achievements at the highest level, it is apparent that Ballarat has always “punched above its weight.” From the arts and sciences, to the upper echelons of business and politics, the city has produced some of the country’s very finest. However, when it comes to sheer determination, few could surpass Harold Berryman.

The eldest son of Richard Baker Berryman and Ballarat-born Mary Ann Polwarth, Harold John Thomas Berryman was born at Ballarat East on 24 February 1884. He was one of nine children born to the couple; they eventually made their home at “Lorna Doone” in High Street, just a block from Lake Wendouree.

Harold’s origins were relatively humble. His father worked as a general labourer and gardener, before working at local implement manufacturer, Kelly and Preston, and the family home was a modest miner’s cottage. But, he certainly inherited a strong work ethic from the Devonshire Berrymans and Scottish Polwarths.

From his early education at the Pleasant Street State School, where he achieved his Merit Certificate, Harold graduated to one of the finest private secondary schools in the State, Ballarat’s Grenville College. His intellectual promise was fostered at the school and he was encouraged to study engineering. So, after just a year at Grenville College he took his first position at the famous Ballarat Phoenix Foundry under the direction of chief draughtsman and engineer, Mr Campbell Laird. He worked as an apprentice fitter and turner at the foundry while he studied engineering at the Ballarat School of Mines and mechanical drawing at the Ballarat Technical Art School. Harold quickly became a popular member of the staff at the foundry, and was very highly regarded by his mentor. At the Company Employees’ Sports in 1901, he also proved he was a good runner by winning the 100-yards dash!

In January 1902, Harold’s exam results for engineering and drawing machines Grade 1 were announced in the local newspapers – he had achieved excellent marks. By 1904 he had successfully passed his course at Grade 3 level and was a qualified engineer. He had certainly impressed Campbell Laird, who gave him a glowing reference.

‘…He is industrious, temperate and reliable and [I] can recommend him with confidence to anyone in need of his services…’

Over the ensuing ten years, Harold built an impressive resumé – after leaving the Phoenix Foundry, he became chief engineer and assistant manager for Dominion Hat Mills in Melbourne, before accepting the position as chief engineer at the Victorian office of Australian Midas Gold Estates. His engineering expertise covered all areas, including electrical, mechanical and structural. He also held three certificates in draughtsmanship.

When Harold left Australian Midas in August 1911, Mr J. W. Tank, General Manager & Director of the company, wrote, ‘…He is very industrious, temperate, honest and most conscientious and willing at all times, and he has proved himself master of his profession. We regret him leaving and can recommend him with the greatest confidence…’

It was obvious that Harold was also developing a keen interest in the newer modes of transportation and quickly became well-known in the motoring fraternity around Australia. He studied internal combustion engines at Gotche’s Technical School and then designed the engines for Bodycombe and Bate.

When war was declared in August 1914, Harold was working for iconic Australian company, H. V. McKay, and was managing the New South Wales branch, as well as being the company’s chief engineer. Despite seemingly being set for life, Harold decided to join up. He attempted to enlist in Sydney, but was rejected ‘…firstly because he had some supposed physical disability, and secondly because he was an engineer…’

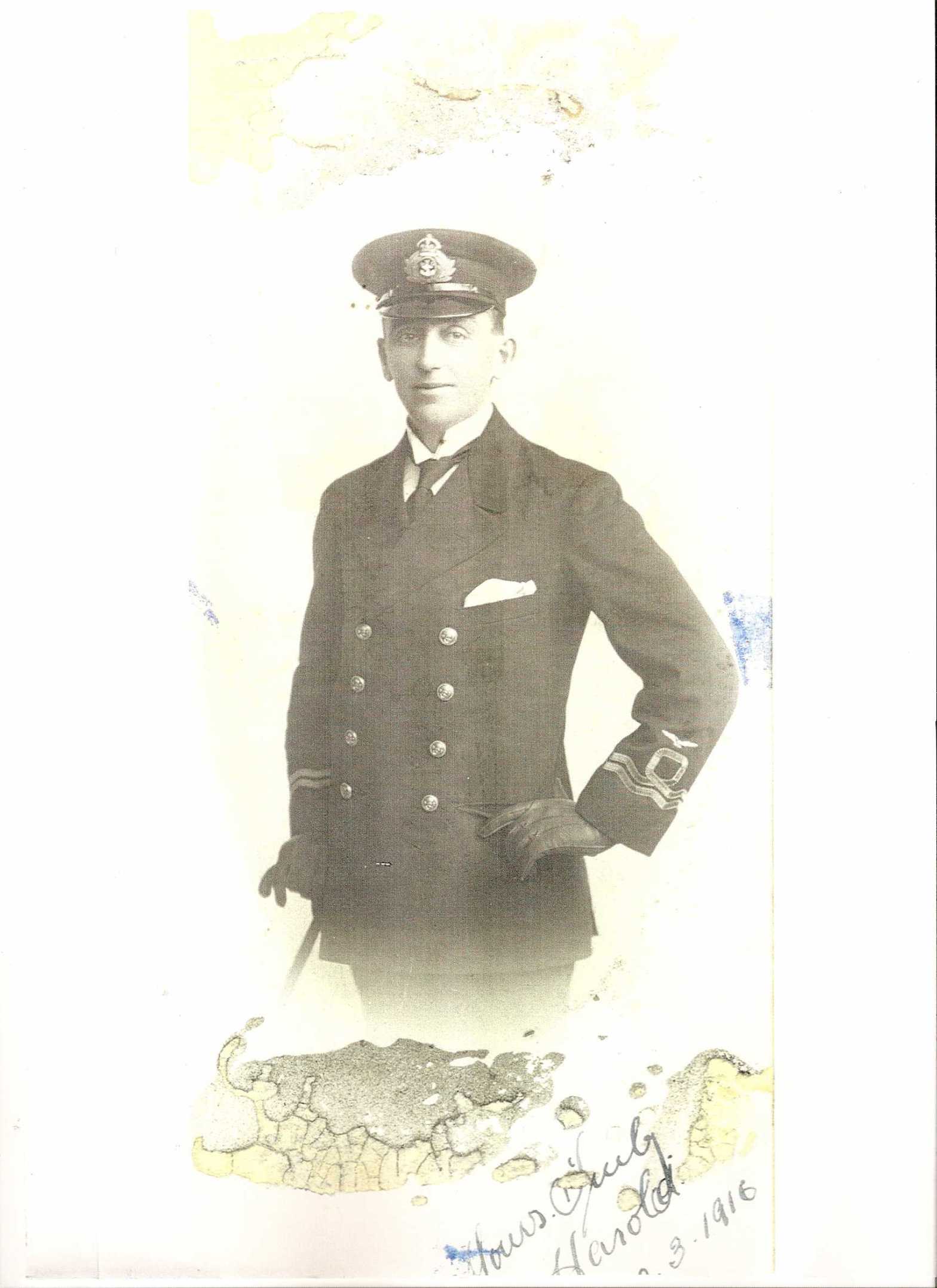

Showing a remarkable level of determination, Harold refused to accept the decision of the Australian military. Resorting to ‘subterfuge’, Harold paid his own passage to England where he was immediately accepted into the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve on 15 February 1916 and commissioned as lieutenant. He was given engineering duties, and quickly began to rise through the ranks.

Writing from London to his mother, Harold painted an extraordinary picture of the life of airman in England particularly during Zeppelins raids.

‘…The airship which we brought down at Cuffley, he stated was the latest type and known the Schutte-Lanz. It is supposed to be superior to the ordinary Zep, being much faster and more strongly built…’

After being four hours in the air, Harold left for Maida Vale to spend the evening. At about 11pm he received a call to return to the station and stand by. Apparently, he could hardly find his way through the dense fog and decided that driving a car was more dangerous in the circumstances than being up 10,000 feet lost in a cloud!

‘…By the time he arrived shrapnel was bursting all around. Five air monsters were discernible and the British aircraft were soon in action, equipped with machine guns and bombs. “We say goodbye to these brave comrades every time they go up at night. They deserve a V.C. every time they land, because they know what to expect when they go up Zep strafing in the darkness of night.

It is the dizzy limit to be 15.000 feet with no one to talk to. London being in darkness and he has no guide beyond a water reservoir in the Thames. When a pilot is about to attack hostile aircraft at night he signals, and our guns cease. Then he ‘bogs’ in and has a lively time. It is a very exciting part to play.

We continued sending up pilots, and gathered up the wrecks of those who landed after being two hours up, all the time, shrapnel exploding pilots chasing the raiders, and the utmost activity being shown in all directions. Accidents were numerous, and the surgeons were kept busy.

Presently another Zep came into sight in close quarters. It was a beautiful sight. The shrapnel stopped and the pilot was left to his own resources. Another 40 seconds and ‘bang’. The raider’s gas bag had exploded at a height of about 8000 or 10,000 feet. To observe this magnificent skill was inspiring, but it was more so to see the mass of flame that fell to earth. We were 10 miles distant, yet the light from the falling airship enabled us to read the paper.

After it reached the earth it burnt out for hours, and you could hear the cheering and yelling from the people who were in the streets in their night attire. Just as taxis were fleeing to the spot with heavy loads, we were warned of another Zep approaching Hendon. It passed over us at a height of about 12,000 feet. These two airships had given London some bombing and were returning practically empty.

Next morning the road leading to the wrecked Zep was congested with every conceivable class of conveyance from the taxi to the lorry. Everyone seemed to have gone mad with excitement, due to the fact that the Zep gets at the stay-at-home fighter and the excuse manufacturer. Of course, someone has to make munitions etc, but it could largely be done with girls and married men.

The wrecked Zep when I viewed it was a mass of charcoal and burnt wires, and the remains of some magnificent specimens of engineering skill and practical work combined. The charred corpses indicated that every man had to be at his post. I counted 16. They had four machine guns and one maxim, but how many bombs they carried I could not say.”…’

The events Harold had described occurred on 2 September 1916, and the pilot who brought down the SL11 Zeppelin using new incendiary ammunition, was Lieutenant William Leefe Robinson. For his exploit, which helped bolster public morale, Robinson was awarded the Victoria Cross.

Just four days later, at Hendon airfield, Harold flew for his Royal Aero Club Aviator’s Certificate in a Curtiss biplane. He continued at Hendon, working on aircraft experiments in the Chief Technical Office.

From Hendon, Harold was transferred to the Isle of Grain with the Royal Naval Air Service. As Officer in Charge, he was responsible for experimental construction in the erecting shops. His flying hours soon included time in box kites, Farman, Curtiss BE, Avro, Bristol Scout, and the Sopwith Pup, Camel and Torpedo.

As Acceptance Officer, with the rank of major, Harold began selecting and testing seaplanes, especially the Fairey N9. He oversaw alterations and modifications to both the engines and the machines themselves.

In April 1918 the RNAS was merged with the Royal Flying Corps to become the Royal Air Force. Harold was then given command of 271 Squadron flying seaplanes. On one occasion he was forced down into the English Channel and spent five hours in freezing waters before being rescued by a British submarine.

During the final stages of the war, 271 Squadron was deployed to the Italian Front. Whilst flying a large air-boat (a 7-ton vessel) over the Adriatic about 10-miles off the Italian coast nearing Cattaro, Harold saw a British torpedo motor boat being attacked by a German submarine. He immediately set a course for the spot, but was too late to drive the U-boat off or prevent the sinking of the torpedo boat. On landing, he found that all but two of the ten crew were missing. Showing remarkable bravery, Harold dived into the rough seas to drag the survivors back to the air-boat.

‘…He had great difficulty in rescuing one, having to kick the man in the head in order to stun him and render him easy to handle, the man having grasped him round the neck, thus endangering the lives of the rescuer and the rescued…’ With the aid of a tow-line, he managed to get the subdued sailor back to the sea-boat and they were both hauled onboard.

The arduous experience resulted in Harold being rested in hospital for two days.

By the end of the war, Harold was the holder of the Air Force Cross. Then, on 1 January 1919, Harold was Mentioned in Despatches in the New Year’s Honours List. It was to be the beginning of a truly momentous year.

Harold had already returned home to Australia when news was received that he had been decorated by King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy on 5 April 1919. The awarding of the Croce di Guerra (Italian War Cross) for Valour was in recognition of his command of 271 Squadron during the Italian Campaign. He was given permission by King George V to wear the decoration and also received the King’s congratulations.

News of Harold’s engagement was leaked to the press on 1 May, although the identity of the young woman was kept secret – she was referred to as ‘the daughter of a well-known Ballarat business man.’ At that stage the announcement had not been shared beyond the families and a close circle of friends. The press, nevertheless, was intrigued…

‘…The interesting point of the affair is that his fiancée has not intrigued in mere flights of fancy; she has actually enjoyed a flight through the ether, and liked the experience so much she might possibly be persuaded to venture an aerial honeymoon, which would he making history so far as Australia is concerned, being the first of the kind. Curiously enough, the young lady had her fly with another Ballarat man as pilot, on which occasion her sisters also ventured aloft, and probably nothing was further from her thoughts at the time than the contemplation of matrimony with an aviator…’

The young lady who was the subject of the newspaper’s intrigue was Miss Florence Annie Farmer, the daughter of George Farmer, proprietor of one of Ballarat’s most prominent businesses. Florrie was the perfect match for Harold – she was bright, fun-loving with the looks of a silent film star.

At the end of May, Admiral Lord John Jellicoe, Commander of the British Fleet, arrived in Australia for a brief tour. Harold, who was now working as the naval representative on the Commonwealth Air Board, was given the honour of being appointed to the admiral’s staff during his visit.

In October, news was received of a further honour to Harold Berryman. He had been awarded the Bronze Medal 1st Class from the Royal Humane Society of Great Britain for the rescue of the two sailors in the Adriatic Sea.

The year was completed when Harold married his beautiful Florrie. Their wedding was celebrated on 27 December at the bride’s home at 158 Eureka Street, Ballarat East. Harold and his bestman, Lieutenant-Colonel J. H. Goble DSC, both wore their uniforms, lending a military air to the ceremony that was performed by the Reverend John Walker from St Andrew’s Kirk. Despite the newspaper speculation that the couple could create history by having an aerial honeymoon, Harold and Florrie chose instead to leave on a leisurely motor tour.

In the early months of 1920, it was confirmed that Florrie was expecting the couple’s first child. They made their home at the St Albans Flats in Blessington Street, St Kilda, to await the birth.

On Sunday evening of 20 December 1920, at a private hospital in Melbourne, Florrie was delivered of a daughter. However, immediately after the birth, Florrie collapsed and died.

Florrie’s sudden death was greeted with shock and ‘quite a gloom was cast over Ballarat East.’ She was of ‘a kind and loveable disposition,’ and ‘a general favourite.’ For many it seemed impossible that this bright, cheery girl was gone. But, for Harold her death must have been devastating. Her funeral was particularly large and attended by politicians, dignitaries, and representatives of many of the large firms in Ballarat. She was interred in the family vault in the Ballarat Old Cemetery.

Harold continued to pursue his career. On 31 March 1921, he joined the Royal Australian Air Force and was promoted to the rank of Honorary Squadron Leader to command No1 Squadron at Spotswood. It was to be a relatively brief association, with Harold resigning his commission on 31 July 1922. It seems he was already envisioning the future of flight in the country.

Raising an infant daughter alone would have been difficult for Harold, but he was fortunate in finding love for a second time. Mary Watson “Molly” Hobbs was said to have been very popular on the Melbourne social scene, but she must also have been a remarkable woman. When she agreed to marry Harold, his daughter (who had been given her mother’s name – Florence Annie – but was to always be known as Bonnie), was not yet two-years-old. But, it seems that Molly was more than prepared to raise the little girl as her own.

The couple were married at the Christ Church in South Yarra on 14 December 1922. A large gathering of family and friends attended the church and all agreed that Molly looked quite beautiful in her ivory satin gown. After the ceremony, the guests were entertained at the Menzies Hotel.

Harold and Molly made their home in Lumeah Road, Caulfield, where they raised Bonnie and even-tually their own three children, Beverley, Richard and Sally.

By the time of Sally’s birth in 1930, Harold was rapidly becoming something of an aviation pioneer. In the late 1920’s he had introduced the Junkers transport aircraft into New Guinea to carry heavy gold-mining equipment into inaccessible areas. Air freight was an entirely new enterprise and the operations saw over 30,000 tons of mining machinery, saw mill equipment, merchandise and livestock flown into the New Guinean goldfields.

Possibly Harold’s most exciting endeavour came in 1935, when he and four other directors, launched Australian Transcontinental Airways Limited, which was registered in Melbourne on 16 Sep 1935. The capital of the company was half a million pounds in £1 shares, and it was the first company of its type in Australia. ATA had been assured by German company, Junkers, that they would supply three large aircraft within six months. However, growing pressure from Herman Goering to supply aeroplanes for the expanding Luftwaffe meant the Junkers reneged on the contract and did not even supply one plane. As a result, ATA ceased operations in 1936, but their results whilst flying two British Monospars and the Southern Moon (sister plane to Kingsford-Smith’s Southern Cross) making the mail run from Darwin into Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney, made it obvious that transcontinental flying was here to stay.

In the years leading up to the Second World War, Harold was factory representative in Australia for Professor Hugo Junkers Aircraft Works in Dessau, Germany; he was also the factory representative for Carl Zeiss Jena Photogrammetry and Aerial Survey technology. His work with this new scientific method of surveying was yet another pioneering achievement.

The respect for Harold Berryman’s ground-breaking work, saw him regarded as something of a prophet. Following on his successful introduction of freight aircraft to New Guinea, Harold planned to extend commercial airways from State to State. He predicted that transporting wool and other heavy products would soon be done by air.

One of his other ideas was the production of flying tanks…

With the outbreak of the Second World War, Harold was determined to offer his services in Australian. On 6 September 1939, he proffered his resumé to the Australian military hoping to be of service to his country. His record was, of course, exemplary. Various military references described Harold as capable, zealous, very energetic, a good pilot with a good command of men. However, it seems that his age was against him and he was not accepted back into the RAAF. Instead, he worked in his own well-equipped workshop carrying out special assignments for the Department of Munitions.

His only son, Richard, enlisted in February 1945 when he was just 18 years-old. Fortunately, the war was over before he could be placed in any danger.

There was general shock when it was announced that Harold Berryman had died suddenly at home late on Thursday 14 June 1951. His many fine achievements were acknowledged in the press. In so many ways he was a man ahead of his time.

Years later, in 2015, a small Bible was rescued from a rubbish dump in Canberra. Inscribed ‘with love’ by a mother to her son on departing for war on 11 November 1915, the Bible had belonged to Harold Berryman. Seeking to return it to the owner’s family involved a great deal of research and not a little luck. Eventually, the book was returned to Harold’s 91-year-old daughter, Beverley, exactly 100 years to the day after her grandmother had written her brief loving message. The pride she felt for her amazing father was palpable – indeed, Harold Berryman was a man of vision who should never be forgotten.

© Amanda Bentley 2019 �Q�